(Outcomes – GR1, PER1,2)

“A contract is based on an exchange of promises.” (e-lawresources.co.uk)

This post details research into contracts and the related agreement between the participants in the Omni-Gaffer film audio project.

In the real world, the agreement between our group would be a business agreement and it is good practice to represent business agreements in the form of a written contract. I have conducted some research into potential contracts which may serve as a template for the one governing our work here, and will go on to discuss the terms and conditions of hypothetical renumeration for the project as well as outlining some of the potential reasons the Omni-Gaffer project is a little more complicated than a standard client – customer relationship. [GR1]

As per my post on intellectual property, I have tended to consider the work we have done for Omni-Gaffer’s clients this term as either services or creative, the distinction being that creative work gives rise to new intellectual property’s such as music compositions as opposed to location audio recording which does not. The copyrights that arise with the creation of these IP’s reside with the creator and must be specifically assigned in order for copies of the works they refer to to be made. This process of assignment can also be applied to revenues created by the works, and it is when this is taken into account that the process of renumerating the group members who comprise Omni-Gaffer becomes more complex.

Dealing first with services such as location audio, we envisioned that Omni-Gaffer would simply split the proceeds of ‘straightforward’ work like location audio equally between the group members. For example, if the location audio service for one film nets Omni-Gaffer £500, then each group member will receive £100 regardless of how much work they did. We chose this agreement for the sake of simplicity in this project and it essentially runs on the trust that none of the people involved are going to deliberately avoid the work in order to, effectively, increase their slice of the pie. Whilst this is fine in the context of a group of people carrying out a uni project who’ve already worked together for the best part of three years, in reality I feel that a better approach to this kind of work would be to simply invoice our hours on set at an agreed day-rate to Omni-Gaffer, as this would reward those who did more or less of the location audio work on the five films accordingly.

The same is largely true of the post-production work – foley, editing and the like – and we also agreed to split reward equally whilst keeping track of the (rough) percentages of work we carried out on each film. This step then enables us to discuss our relative worth to the project, and would further enable us to agree if any particular member of the group had let the side down in terms of the work carried out. A contractual stipulation to the effect that a majority of the group can alter the percentage of renumeration at the end of the project could then be incorporated into a hypothetical contract, though I suspect this would be difficult to actually enforce.

The situation becomes more complex when new IP’s and copyrights being created in the course of the work. These potentially have a longer income tail, and copyrights reside with the original author unless specifically assigned in writing. This complicates the situation in two ways – firstly, a song which is composed for a film without payment (as opposed to one which is composed for a payment which is considered to be the property of the film-maker because it is commissioned) could later make money if used, for example, in another context. Since the Omni-Gaffer group has effectively enabled the creation of this song, a claim by those parties could be made for any future royalties. We dealt with this by agreeing that each composer would agree a percentage of all revenue from any song composed for OG projects be paid to the collective, and thus split equally between the partners. This issue of assignment also speaks to another issue which would need to be addressed, since the five parties who make up Omni-Gaffer also need the ability to agree to assign usage rights for music compositions to the film-makers to whom they are providing the services. I would suggest that a written agreement between the composer and OG also enable this process to take place as required, subject to a suitable system of checks and balances (ie, one member of the group can’t agree to things without the others say so). [PER1,2]

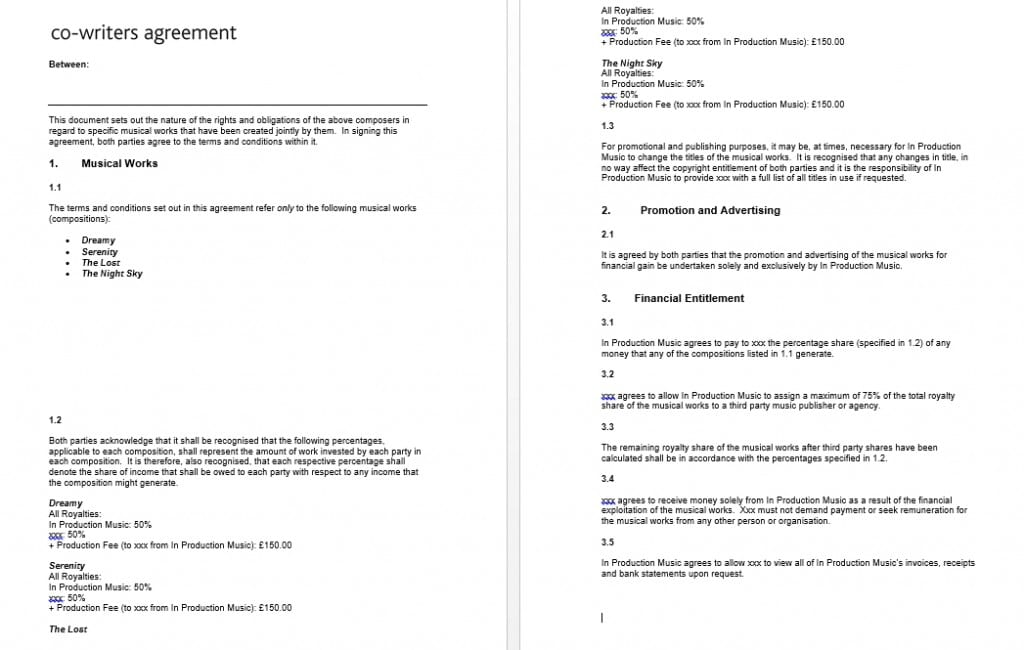

Secondly, a song which is composed for a film may be the product of a collaboration which is based on relatively vague discussions or directions from multiple parties (as opposed to “I wrote the drums, you wrote the guitars,”. An example of this exists in Immort’s street scene – I suggested to the composer during an impromptu discussion that he include an arpeggiated synth line in the track, to give it a more 90’s vibe. I could therefore argue that I ‘wrote’ an aspect of the piece, and am entitled to a share of any future profits it generates. This requires an agreement between whichever parties created the song, and is something that would need to be arrived at and agreed in writing between these parties outside of the Omni-Gaffer collective, like the one displayed here which is used by our tutor for this project in his day to day business. In the case of the song in Immort, I do not consider my own contribution to have been worthy of any claim to the composers work and I’m not aware of any collaborations of this type which took place during the project, and which would have required a formal writer’s agreement. [PER 1,2]

Another key concept in contract law of interest here is that of consideration –

“In contract law consideration is concerned with the bargain of the contract…Each party to a contract must be both a promisor and a promisee. They must each receive a benefit and each suffer a detriment. This benefit or detriment is referred to as consideration…Consideration must be something of value in the eyes of the law,” (e-lawresources.co.uk)

Since no money is changing hands in the context of this project, it is necessary to define exactly what the consideration upon which a contract in the academic context is based. On the one hand, we are promising our labour on the projects in question to the film-makers, but the ‘currency’ being traded between the five parties comprising OG is a little more obscure. We’ve variously discussed a solution to be academic marks, and / or the rights to utilise the finished products as portfolio pieces in the future. Both of these are fraught with complications, but logically the fairly democratic and even-handed structure we’ve settled on would best suit the latter – Those who put in a share of effort on the films get to exhibit as portfolio the ones with which they may have had less to do with the production of in the future. [PER 1,2]

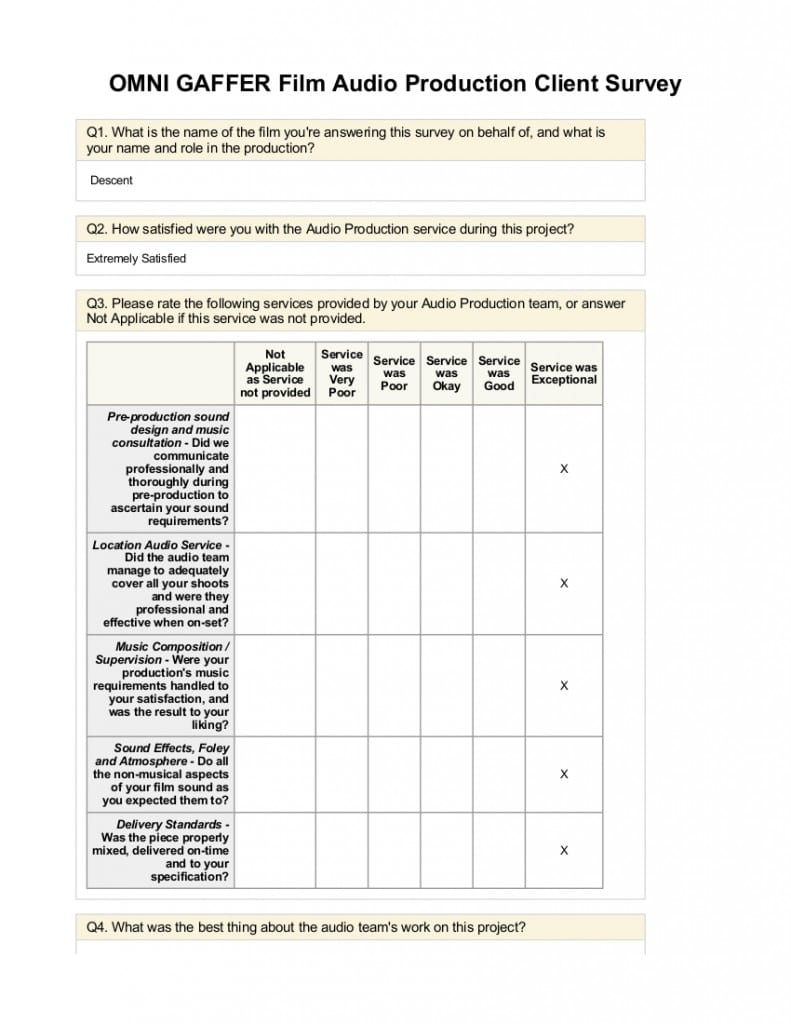

There is much more to say here, but in the interest of word count I must digress here. Whilst our contractual positions may be fairly complex, they are nothing compared to some of the contracts we’ve received from the film-makers, who appear to simply hand out anything they’re given by their tutors without even a cursory inspection. Examples can be found in supporting material, but one example appeared as we approached deadline in the form of a document which was extremely heavy on the legalese, and which requested that we supply masters of our audio on DAT and audio tape suggesting it was somewhat out of date. An overhaul of the LSM contract archive is probably in order.

————————————– 1300 words

KEY POINTS –

Breakdown of potential contractual issues with Omni-Gaffer project – Professional practice

- [GR1] To professionally operate as a small to medium size company (or other recognisable business entity) in the audio production / post-production field might.

Research into examples and contract law – Research

- [PER1] To develop a better understanding of the pros and cons of business structures, processes, regulations and agreements which might enable film audio producers to collaborate on multiple projects.

- [PER2] To develop a better understanding of the wording and content of contracts, rates and rate cards offered in the film audio field.