(Outcomes – IN2 + GR3)

Part of a dub mixer’s job is to deliver mixes of programs to particular technical specifications. In the case of programs for broadcast, the current European standard is EBU R128, a set of rules regarding loudness normalisation and permitted strength of audio signals. As part of another module this semester we interviewed staff at Soho Square Studios, one of whom explained to us that knowledge of working to this standard is very much sought after in the post-production industry.

The dub mix I carried out for our project last term conformed to the BBC’s guidelines for production. This term, I’ve suggested to our directors that all our output should conform to the newer R128 broadcast standards – they have no particular requirements, so this is as good a choice as any.

The essential difference with R128 mixing is that it requires reference to the overall loudness of the piece over it’s entire length as an average, where BBC guidelines I have employed previously simply control the audio peak levels within the program regardless of it’s average loudness. The changes were wrought mainly to deal with advertisers using the perception of loudness (through compression, and rather than the mathematical loudness inherent in the audio) to create irritating volume changes relative to a given program. Practically, it enables higher highs and lower lows across the course of the program, but controls the volume across the course of the bulk of the output.

EBU R128 changes the unit of measurement of mixing from decibel or PPM to loudness unit, and requires that the mixer bring the average loudness of the piece in between 22 and 24LU by it’s completion. It also measures peaks within the audio waveform much as with the BBC method, and requires that none of these surpass 1.0 on the true peak scale. There is also a loudness range requirement which must not exceed 95%. [IN2]

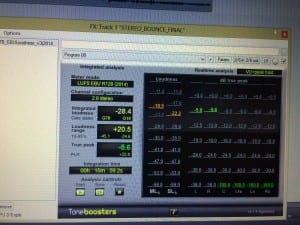

I purchased a metering plugin which is R128 compliant, and ran the mix I created last term through it for reference –

As we can see, this piece would not comply with R128 as it too quiet on average by 4.4LU even though peaks etc are within range.

Having completed the mix of Descent to the previous BBC guidelines, results were –

This was both too quiet on average (27.1), and contained a couple of sharp peaks (0.3) which are too aggressive for broadcast. I remixed the latter and ran another mix –

As you can see, this mix is *only just* within the compliance threshold for average loudness, though the peaks are now well within the line. I deemed this sufficient as I was extremely pressed for time by this point.

Working to R128 is industry standard for broadcast in the UK and as such is an extremely useful to have learned – it was referred to during an interview with a professional audio engineer for another module as one of the most important things to know about – and it’s interesting from the perspective of the mix process, since it enables a less slavish monitoring of PPM metering and a freedom to push big sounds more aggressively for impact. Descent was not really the film on which to demonstrate this last technique since it is one which uses realism and more subtle light and shade, but I think the process will inform future sci-fi work I undertake, if nothing else. [GR3]

—————————————— 500 words

Key Points –

Research and the practice of dub mixing to R128 – Research, Application of skills and conduct in production.

- [IN2] To develop a better understanding of the craft and industry of a Dubbing Mixer, and to contribute to the dub mixing required for presentation of the artifact – (Dubbing Mixer)

Reflection on usefulness of research and practise – Individual reflection

- [GR3] To provide a professional standard of service in respect to location sound recording and post-sound design / mixing.